week of

February 1-7

introduction

How do materials get their shape?

The two most important building materials to emerge from the eighteenth-century Industrial Revolution in England, iron and glass, were not new materials per se; in use for centuries, they were newly produced at a quantity that made them relatively affordable. Still applied in sparing quantities, only in the nineteenth century did they "emerge" in a way, becoming part of the professional and public debate about materials and the extent to which they should be included in defining what was "real" architecture--especially in light of expansive public works projects entrusted to engineers, who were defining their vocational jurisdictions at the same time as architects were. This complicated state of affairs meant that the developing definition of the profession of architecture (and expectations for its practitioners' training/preparation/education), theories of architectural values and criteria for judgement, and considerations of how to handle "new" materials, are three strands of a tight cord that represents architectural developments in the mid-nineteenth century.

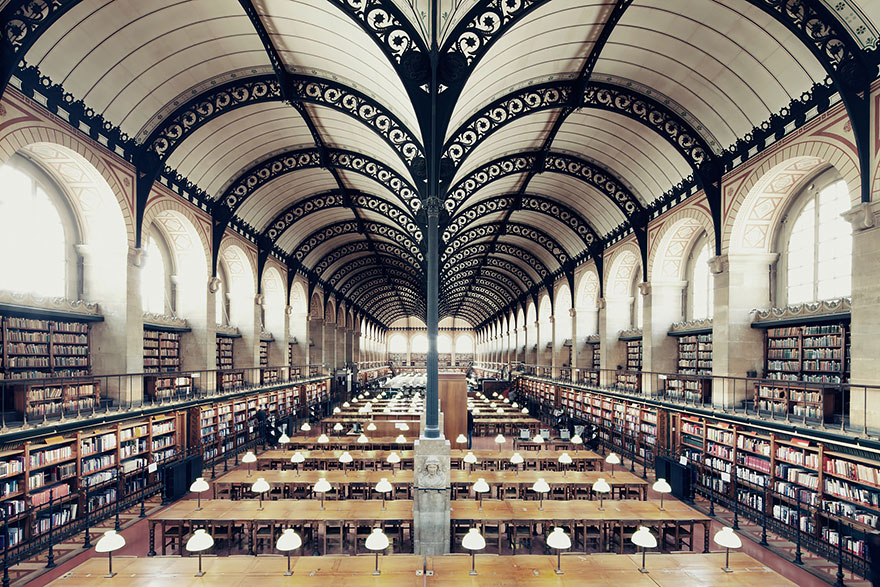

Central to the argument was iron, both cast and wrought, famously exposed to public view at the monumental Coalbrookdale Bridge in 1781, and less-famously employed in mills and factories for interior vertical support (primarily), and other concealed applications where it assisted architects' deployment of masonry vaults for reasons of stability and fireproofing within Grecian forms that otherwise could not abide the subsequent lateral forces (see Soufflot's Ste.-Geneviève, started in 1755, and Strickland's Second Bank of the US, 1818). Architects increasingly used, and exposed, the material through the mid-nineteenth century, raising the question, based in longstanding familiarity with traditional forms and proportions borne of the structural capacity of materials like timber and stone: just what should this fabricated material, with no natural/organic shape, look like? Was it best bent into efficient shapes of extreme elasticity, or cast and hammered into familiar forms historically manifest in other materials? And, once in a shape, how to protect this material that was highly corrosive and required a covering to keep it from rusting? What was iron's proper color? Among the scores of buildings that provide interesting case studies here, the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève (Paris, 1838-50) and Crystal Palace (London, 1850-51), are especially helpful, famous buildings that will serve as our focus, while the writings of Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, John Ruskin, and our old friend Pugin, contribute importantly to the discussion as well.

The way that engineers, architects, critics, and the public answered that question--in the nineteenth century, through the twentieth and into ours--is largely dependent on a stance based into the foundational themes for this class: social constructivism and technological determinism. Before proceeding much farther into the new material,

and to prime yourself for this lesson in the material and theory of architecture in the nineteenth century,

- Read: Bergdol, chap. 6 (skim most; read pp. 179-189); read chap. 7

- Review: Gelernter, chap. 5 (pp. 153-57)

You may wish to preview the entirety of the lesson before taking it on bit by bit, since at the end you will be asked to summarize a lot of this information into one short essay. Also, to prepare for it, you need to organize yourselves into peer review pairs (and one triple). If you'd like to select your own partner, do so through the link below.

learning objectives

At the conclusion of this lesson, you should be able to:

- Identify main nineteenth-century monuments by name, date, designer/client and location (KNOWLEDGE)

- Define terminology specific to technique, style and structure (KNOWLEDGE)

- Describe integration of technology (especially cast and wrought iron) in individual monuments (KNOWLEDGE)

- Explain stylistic/technical changes in design as they relate to cultural context (COMPREHENSION)

- Summarize the main concepts in important works of theory by Viollet-le-Duc, Ruskin, and Pugin (COMPREHENSION)

- Visually analyze buildings from this period to suggest date, place, and designer (ANALYSIS)

- Critique the agency of people and technology within the process of design (EVALUATE)

part 1

Materials

To get started, let's see how much you remember about this period, and its themes, from ARC 232 (or its equivalent).

Once you're reacquainted with some of the central nineteenth-century issues, let's move on to the main materials of its first half.

Iron

Used sparingly in the ancient period (due the difficulty of managing it, and the resultant high costs), iron was made more economically viable in the mid-eighteenth century, due to the efforts of the Darby family. The first great monument of cast iron was a bridge built as much as an advertising mechanism than as a work of infrastructure.

Iron was quickly adopted into very pragmatic applications: providing slim, fireproof supports in mills and factories, and slowly making its way into public/civic applications. Yet it would be some time before it became acceptable as an exposed design element within architecture.

Iron was only one of many new materials that became more widely available during the growth of industry in western Europe and the United States. In the metallic realm, steel would follow iron by the 1870s but, like iron, had a "questionable shape" (to quote a theorist of the day) and was seen as an adjunct, at best, to real architectural materials, based on longstanding traditions and aesthetic expectations.

Glass

Buildings had been glazed with all sorts of materials, from fat-smeared parchment to thin slabs of alabaster. Glass was historic, and historically expensive. The creation of rolled-plate-glass, pioneered by the Chance Brothers in 1832, allowed for bigger pieces of glass to be produced reliably and (relatively) inexpensively. The following video may give you pause as you consider how cheap and easy it might have been to make glass.

Terra Cotta

Although it comes into its own a bit later in our timeframe, terra cotta is worth introducing at the moment, since it has much in common with iron and glass. Although this video shows more recent approaches to the design and manufacture of terra cotta elements for architectural use, its concepts and general approach to production replicates that of the nineteenth century: determining color and shape through a collaboration between designer and fabricator, modeling and molding based on an architect's drawing and the fabricator's experience with, and understanding of, the material, and the general casting process (given different technologies, of course). The materials and energies remain the same, although the technology of communication and production have changed.

part 2

Theory

For every architectural theorist, critic, and journalist working in the mid-nineteenth century, there were just as many opinions about what to do with the potential of these new materials. In particular, iron posed a significant challenge and received the greatest attention. It offered obvious opportunities for efficient, fireproof (or, rather, fire-resistant) construction, but also had no clear precedent for being used aesthetically in design. Consider this variety of theorists:

- Pugin, who writes in Principles (1841) about the primacy of "convenience, construction, or propriety" and the proper role of ornament, and explains why cast-iron is always a "deception;" in the Apology (1843) he reiterates some of these ideas within an overview of architecture's traditional historic and cultural meaning, while commenting on the nature of invention in medieval and modern architecture.

- In two of his six-part lecture series, Walter explains the "two-fold character" of architecture: it is useful and imaginative, which suggests that architects might take a different stance toward each; while not commenting on iron directly, he does focus on the idea of modernity, and the particular character of contemporary architecture within a historic framework, which has important implications on this lesson.

- Ruskin's Seven Lamps of Architecture (1851) includes some of the century's most famous admonitions against iron, building on Pugin and stating the many ways it violates the virtue of truth.

- In a long series of lectures, Viollet-le-Duc returned to the issue of iron and structural design time and again; in the provided excerpt you'll read his version of "truth" in architecture, which affects the planning and structural design of a building, as well as choices about materials.

part 3

Practice

Watch the following videos that summarize and build upon the readings you've already done on these two important monuments: the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève in Paris (Henri Labrouste, 1838-51) and the Crystal Palace in London (Joseph Paxton, 1850-1).

Finally, review the great resources on the construction of the Crystal Palace provided through contemporary reporting and housed on the Victorian Web.

Application

Choose one of these two buildings as the focus of an essay that places it within its historic context and analyzes it from two points of view described earlier, and provides a personal evaluation of the framework. In short, your essay should have three parts:

- brief history and provision of context, drawing from the many materials provided in this lesson (the lesson text on this webpage, textbooks, videos, and theory excerpts);

- analysis of technical change/use of iron from social constructivist and technological determinist points of view; and

- your evaluation of the two points of view, stating which you think is most accurate/helpful, and why.

You will note that point (1.) relates to course learning objectives related to knowledge, understanding, and comprehension; (2.) is more deeply about comprehension and (3.) gets to evaluation.

Essays shall be no more than 1,000 words long. In lieu of a cover sheet, simply include your name, the course number and date in a header. Provide a title for your essay that indicates its thesis. For foot/end-notes, use the latest edition of the Chicago Manual of Style and use the “Notes and Bibliography” format.

- Due: Email your paper, as an attachment in Word, to Dr. Amundson and your peer reviewer(s) by Wednesday at 1 PM.

- Use this rubric as you develop your paper to make sure that you have addressed the requirements of the assignment.

additional resources

Quiz

See instructions from the last lesson.

Image at the top: Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, Paris (Henri Labrouste: 1838-50)